Business Roundtable welcomes this hearing on the Ways and Means international discussion draft as part of the Committee's broader objective of comprehensive corporate and individual tax reform.

Business Roundtable (BRT) is an association of chief executive officers of leading U.S. companies with over $6 trillion in annual revenues and more than 14 million employees. BRT member companies comprise nearly a third of the total value of the U.S. stock market and invest more than $150 billion annually in research and development -- nearly half of all private U.S. R&D spending. Our companies pay $163 billion in dividends to shareholders. BRT companies give nearly $9 billion a year in combined charitable contributions.

Business Roundtable commends Chairman Camp for his leadership in putting forth a detailed corporate tax reform proposal to address many of the deficiencies of the current tax system in order to provide for a stronger domestic economy with increased investment, increased employment, and growing wages. The proposal provides the essential components to a reformed corporate tax system, including a commitment to a significantly lower statutory rate and a territorial tax system.

Reform of the U.S. corporate tax system and its treatment of international income are of significant importance to the growth of the U.S. economy. U.S.-headquartered companies with operations both in the United States and abroad directly employ 23 million American workers and they create over 40 million additional American jobs through their supply chain and the spending by their employees and their suppliers. The ability of American companies to be competitive in both domestic and foreign markets is essential to improving economic growth in the United States, reducing high rates of U.S. unemployment, and providing for rising American living standards.

The U.S. corporate income tax system today is an outlier relative to the tax systems of our trading partners at a time when capital is more mobile and the world's economies are more interconnected than at any time in history.

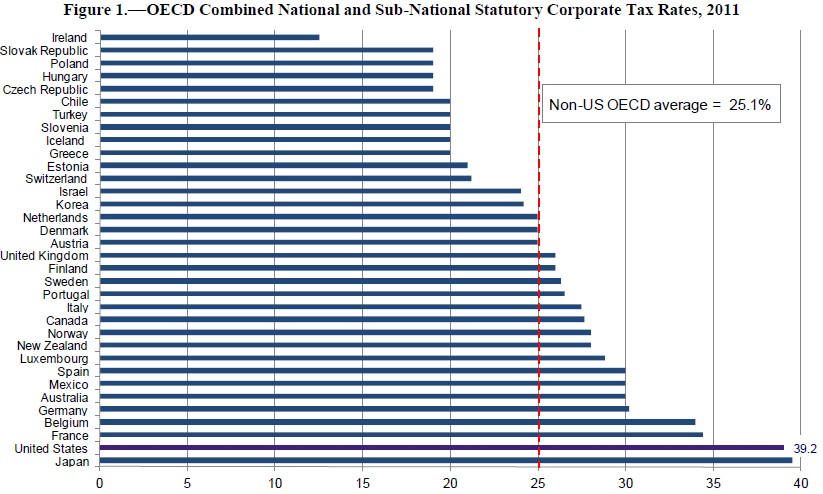

The combined U.S. federal and state statutory corporate tax rate is the second highest in the OECD, and will soon be the highest rate following anticipated reforms in Japan in 2012. A significant reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate is an essential element of meaningful corporate tax reform.

The United States is also the only G-7 country that taxes the worldwide income of its corporations, with Japan and the United Kingdom having adopted territorial tax systems in 2009. Within the OECD, 26 of the other 33 countries use territorial systems for the taxation of foreign earnings.

Under territorial systems, a domestically headquartered company pays the same rate of tax on its active foreign earnings as do other companies operating in the foreign jurisdiction but it owes no additional tax when it brings back foreign earnings for reinvestment in its home country. In contrast, under worldwide tax systems, the domestically headquartered company owes additional tax to its home country on dividends of foreign earnings if the domestic rate of tax exceeds the foreign tax rate on its foreign earnings. High tax rate countries that use a worldwide system subject the foreign earnings of their domestically incorporated multinational corporations to tax from two taxing jurisdictions.

The combined effect of the high rate of U.S. corporate tax and the worldwide U.S. tax system makes it more difficult for U.S.-headquartered companies to compete effectively in foreign markets, reduces the reinvestment of overseas earnings back into the United States, and discourages new investment in the United States by both U.S.- and foreign-headquartered companies.

Since the time of the last major reform of the U.S. corporate tax system in 1986, the world's economies have become increasingly integrated. The importance of cross-border trade and investment has grown significantly, with worldwide cross-border investment rising six-times faster than world output since the 1980s. Today, the U.S. corporate tax system hinders the ability of U.S. companies to grow and compete in the world economy with the consequence of less investment in the United States and a more slowly growing economy with fewer job opportunities for American workers. The ability of American companies to compete and invest abroad is vital for opening foreign markets to U.S.-produced goods and expanding the scope of investments in R&D and other activities in the United States.

The discussion draft released by the Ways and Means Committee on October 26, 2011, represents a significant step towards modernizing the U.S. corporate income tax system. Below are Business Roundtable's comments on the major elements of the Committee's discussion draft.

1. 25% Statutory Corporate Tax Rate

The discussion draft proposes a 25 percent federal statutory corporate tax rate, beginning in 2013, a 10 percentage point reduction from the current 35 percent rate. By bringing the U.S. rate much closer to that of our major trading partners, the reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate on its own would significantly increase the attractiveness of the United States as a location for new investment and for earning income for both U.S.- and foreign-headquartered companies.

Rate reduction can also reduce distortions that arise under an income tax, including reducing variations in effective tax rates across alternative investments and reducing the tax incentive for the use of debt relative to equity financing.

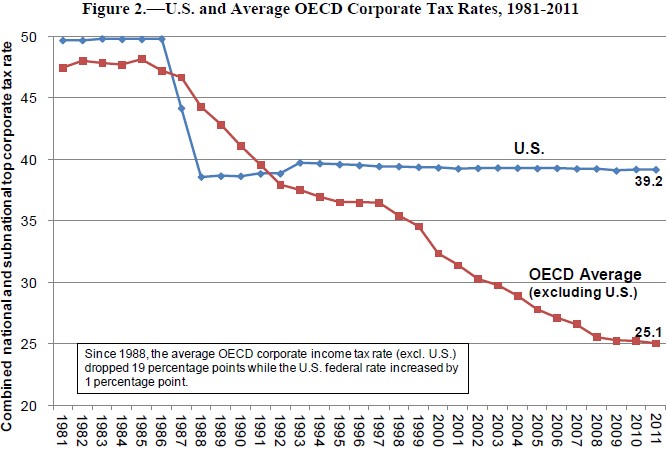

Including federal and state income taxes, the U.S. statutory tax rate of 39.2 percent is the second highest in the OECD in 2011 (see Figure 1). Based on OECD data, had the 25 percent federal rate been in effect in 2011, the combined U.S. federal and state tax rate would have been 29.8 percent, and would have resulted in the United States having the eighth highest statutory tax rate in the 34 country OECD. The average combined statutory tax rate in the rest of the OECD in 2011 is 25.1 percent. The average OECD corporate tax rate has fallen by more than 10 percentage points since 1998 and by more than 19 percentage points since 1988 (see Figure 2).

Source: OECD Tax Database and PwC Worldwide Tax Summaries, http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/worldwide-tax-summaries/index.jhtml, and Note: Estonia tax rate shown for distributed income (retained income is exempt).

Source: OECD tax database. The U.S. rate is based on the 35 percent federal tax rate and average state taxes of 6.44 percent, which are deductible from federal taxes.

Although not as widely noted as the high statutory corporate tax rate, the United States also has a high effective tax rate on corporate income. A study of financial statement effective tax rates for the 2,000 largest companies in the world found that U.S.-headquartered companies faced a higher worldwide effective tax rate than their counterparts headquartered in 53 of 58 foreign countries over the 2006-2009 period.1

The summary materials released by the Ways and Means Committee in conjunction with the discussion draft state that the statutory rate reduction is intended to be undertaken with other reforms to provide for revenue neutrality. Business Roundtable supports the need to undertake tax reform within an overall environment of fiscal consolidation, including spending cuts that will reduce projected future deficits. When considering the revenue effects of tax reform, however, it is important to take account of the revenue feedback effects from a more competitive corporate sector and faster growing economy. The best way for the government to increase tax collections is through economic growth, not higher tax rates. Further, while base broadening measures may include the repeal of provisions that no longer serve their intended purposes, it should be recognized that some tax expenditures or other preferences serve an important role in increasing investment.

Nevertheless, a reformed tax system -- with significantly lower statutory corporate tax rates, a stable tax code, and greater neutrality across alternative investments -- can result in greater economic growth and greater job opportunities for American workers.

2. Establishing a 95% Dividend Exemption ("Territorial") System

The discussion draft proposes a territorial tax system under which 95 percent of active foreign-source dividends paid by controlled foreign corporations to 10-percent or greater U.S. C-corporation shareholders effectively would be exempt from U.S. taxation, provided the specified one-year holding period requirement is met, effective in 2013. At the proposed 25 percent statutory corporate tax rate, the 95 percent exemption would result in a tax rate of 1.25 percent on foreign dividends.

The discussion draft provides an important starting point for the move to a territorial system for the United States. The proposed territorial tax system, however, is built around many existing U.S. international rules and there are many details in the proposal itself that require close examination. This is a complex area and it is critical to the international competitiveness of many U.S. companies that it be done right. We commend Chairman Camp, Chairman Tiberi, and the other members of this committee for seeking input from taxpayers, scholars, practitioners, and the public at large on the discussion draft. This submission provides our initial comments on major features of the proposed system, but our member companies will continue to examine the legislation and we intend to provide more detailed comments on other aspects of the proposal soon.

A territorial tax system structured similarly to the territorial tax systems of other OECD countries is essential for U.S.-headquartered companies to be competitive in foreign markets and have the same ability to reinvest foreign earnings at home as their competitors.

It is the experience of our CEOs that expansion of U.S. companies abroad into foreign markets increases employment at home and exports of U.S. produced goods and services into the foreign market.2 A properly designed territorial tax system would increase the competitiveness of American companies in foreign markets and make U.S. companies stronger at home.

As shown in Figure 3, 26 of the 34 OECD countries use territorial tax systems, with 18 of these countries providing a 100 percent exemption for foreign-source dividends. The lowest exemption is 95 percent, used by seven OECD countries. The 95 percent exemption typically results in a tax rate of 1 to 2 percent on the foreign dividends in these countries (e.g., in Germany, 5 percent of the dividend is subject to a 30 percent tax rate, resulting in a tax equal to 1.5 percent of the remitted income). Norway uses a 97 percent exemption standard, which results in a tax rate of approximately 0.8 percent on foreign dividends.

In contrast to the current U.S. tax system, a territorial system allows foreign earnings to be reinvested at home at little or no tax cost. It is estimated that between one and two trillion dollars of foreign earnings of U.S. multinationals is currently reinvested abroad, some of which would be expected to be immediately repatriated for use at home if a territorial tax system were enacted. The territorial tax system would be expected to result in a much larger percentage of future foreign earnings being repatriated for domestic uses by U.S. multinationals than would occur under present law.

The use of less than a 100 percent exemption by several of the OECD foreign countries is sometimes justified as in lieu of any disallowance of domestic expenses that indirectly relate to the foreign earnings of a corporation. While a small reduction in the exemption below 100 percent is unlikely to create a repatriation barrier, some question whether in fact any such reduction is justified.3

Limitations on the deduction of domestic costs for these indirect overhead activities generally are not a feature of other territorial tax systems, and the United States should not seek to include such a limitation as part of the adoption of a territorial tax system. While some reduction in the exemption percentage is tolerable as a means of revenue generation under the territorial tax system, in no case should the exemption percentage be less than 95 percent, the lowest exemption rate found in the OECD.

The application of territoriality to foreign branches of U.S. companies is another area of complexity with significant potential unanticipated consequences. In some cases companies are required to operate in foreign countries via branches as opposed to foreign subsidiaries. Alternatives to mandating treatment of branches as foreign subsidiaries must be considered to avoid non-competitive treatment of certain foreign operations.

3. Anti-Base Erosion Provisions

The discussion draft proposes three alternative options intended to address concerns that a territorial tax system would potentially result in a shifting of some income and activities from the United States to low-tax foreign jurisdictions.

Business Roundtable agrees that the movement of any U.S. activities abroad for the purpose of avoiding U.S. income tax is antithetical to the intent of a territorial tax system to increase U.S. economic competitiveness and employment. As noted above, it is the experience of our member companies -- and also the findings of economic research -- that foreign activities of U.S. companies on balance complement their domestic investment and employment, so that a territorial tax system should enhance U.S. economic growth, in addition to encouraging the repatriation of foreign earnings for domestic uses.

A concern with the development of any anti-base erosion provision is the difficulty of identifying activities that are undertaken abroad for tax rather than other business motivations such as: cost savings from operating closer to foreign consumers, the presence of local natural resources, and specialized labor, among other factors. Further, certain foreign business structures can help reduce income taxes paid to foreign countries, and are often used by competitors. As a result, anti-base erosion rules that are unlike those adopted abroad can impede the competitiveness of American companies relative to their foreign competitors.

For this reason, any rules which limit the basic application of the territorial system in an effort to reduce income shifting opportunities must be narrowly focused on potential abuses that would result in a reduction of U.S. income tax. Rules that put U.S.-headquartered companies at a competitive disadvantage and result in the loss of sales by U.S.-headquartered companies would be counterproductive to the goal of a territorial system. Care also should be taken to avoid adoption of rules that impose excessive administration and compliance costs.

Each of the three anti-base erosion options proposed in the discussion draft potentially have broad application and have the potential to adversely affect some current overseas operations of U.S. companies that by definition are not motivated by the potential tax savings of a territorial tax system. Some have described the three options as more consistent with the repeal of deferral than the adoption of a territorial tax system.4

Business Roundtable appreciates the concern for potential base erosion under a territorial system but believes further dialogue is needed to identify the specific new tax planning opportunities that potentially would arise under a territorial tax system and the experience of other countries with territorial tax systems.

4. Certain Active Business Income Remaining Subject to Anti-Deferral Rules

The discussion draft does not address the temporary provisions that allow deferral of certain active finance income (income derived from the active conduct of banking, finance, and insurance) and of income received from related foreign affiliates ("CFC look-through"). Business Roundtable believes that these temporary provisions should be made permanent under a territorial system. The active financing income rule treats active business income of financial companies in the same manner as active income of non-financial companies. The "look-through" rule treats payments between related foreign subsidiaries as active business income where the underlying earnings are not subject to current U.S. taxation by virtue of arising from active business income.

In addition, Business Roundtable believes the current law subpart F rules should be further modified to exclude foreign base company sales, service, and oil-related income. Consistent with the fundamental principle of a territorial tax system, this would permit these foreign business activities to be competitive with foreign-headquartered companies. Safeguards consistent with those applied by other countries with territorial systems may be adopted, if necessary, to address any concerns for potential U.S. base erosion.

5. Interest Deduction Denial

The proposal would deny a deduction for U.S. interest expense where the U.S. company's debt ratio exceeds the global debt ratio of its worldwide group and its domestic interest expense exceeds a yet to be specified percentage of its adjusted taxable income. The proposal would apply to both related and unrelated party debt and would be in addition to current interest limitations applying to related party debt in sec. 163(j).

As described in the Ways and Means Committee document, the intent of the proposal is to prevent disproportionate interest deductions in the United States by U.S. multinationals that erode the U.S. tax base.

The use of thin capitalization rules to limit deductions for interest payments on related party debt is relatively common across countries, although limitations on unrelated party debt are less common. Application of the thin cap rule to unrelated party debt broadly expands the scope of the limitation and therefore should be appropriately tailored to not limit interest deductions that would be expected to arise under normal business considerations. There may also be non-tax operational reasons to justify a higher level of debt in the United States relative to a company's global leverage.

Cyclical businesses may find that their interest expense is large relative to adjusted taxable income during periods of low profitability. In addition to providing a carryforward of denied interest expense, businesses should be allowed to carry forward excess limitation during periods when profitability is high relative to interest expense. The current law sec. 163(j) interest limitation rules provide both such carryforwards, although a longer carryforward period of excess limitation is appropriate under the proposed thin cap rule given its broader application to both related and unrelated party debt.

6. Transition Tax on Pre-Enactment Earnings and Tax on Previously Taxed Income

The proposal would subject pre-January 1, 2013, deferred foreign earnings of 10-percent or greater owned foreign companies to a 5.25 percent tax rate.5 The tax is payable in equal annual installments over up to eight years, with an interest charge. In addition, if such earnings are repatriated to the United States, they are subject to the 95 percent exemption system under which a 1.25 percent tax would be levied.

Any transition to a new tax system requires rules for determining how pre-effective date tax attributes are to be accommodated. Significant simplification is achieved by treating pre-effective date earnings in the same manner as post-effective date earnings. Countries recently adopting territorial tax systems, including the United Kingdom's 100 percent exemption system and Japan's 95 percent exemption system, have made pre-effective date earnings fully eligible for their territorial tax systems.

The proposal makes no distinction between foreign earnings that have been reinvested in foreign operations and foreign earnings held as cash or equivalents, nor does it consider whether or not the company has previously declared in its SEC financial statements that such income would be indefinitely reinvested in its foreign operations.

In addition to this transition tax, previously taxed income and future subpart F income (which is taxed on a current basis in the United States) will also pay an additional 1.25 percent tax upon repatriation.

We are unaware of any country that imposed a transition tax on prior earnings when it adopted a territorial tax system or any country that does not fully exempt repatriation of foreign income that has already been subject to domestic tax. Consequently, Business Roundtable recommends further consideration be given to whether there are compelling reasons to depart from international norms.

7. Conclusion

Business Roundtable appreciates the consultation process initiated by the Ways and Means Committee through this hearing and the release of the October 26 discussion draft. The discussion draft reflects important progress toward the adoption of a competitive territorial tax system in the United States and a commitment to a lower statutory corporate rate that is critical to increasing the global competiveness of U.S.-based businesses and increasing the attractiveness of the United States as a location for investment.

Business Roundtable commends Chairman Camp, Chairman Tiberi and the members of the committee for undertaking this serious effort toward much needed reform.

On behalf of Business Roundtable, I look forward to working closely with this Committee toward this important goal.

End Notes

1 "Global Effective Tax Rates," April 14, 2011, available at studies-andreports/global-effective-tax-rates.

2 This finding is also supported in economic research. One study finds that a 10 percent increase in sales and foreign employment by a U.S. company's foreign subsidiaries results in an increase in exports of goods from the United States and an increase in U.S. employment by the American company of 6.5 percent (see Mihir Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines, Jr., "Domestic Effects of the Foreign Activities of US Multinationals," American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, February 2009).

3 See, Statement of Paul W. Oosterhuis, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, "Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures of the House Committee on Ways and Means," November 17, 2011. The basic argument in favor of limiting the exemption is that under a "matching" principle, deductions giving rise to exempt income should be disallowed. It should be noted that domestic expenses that directly support foreign activities are required under current law to be charged out to the foreign subsidiary and are fully taxable at home (and would remain fully taxable under the proposed territorial tax system). As a result, only domestic expenses that indirectly support foreign activities are at issue, such as interest expense, R&D, and general and administrative expenses. However, such indirect expenses arising in the U.S. would not be allowed to be deducted in the foreign jurisdiction even if the deduction were disallowed in the United States. In the case of interest expense, "thin cap" rules (discussed in more detail below) can more appropriately ensure that the domestic corporation is not excessively debt financed relative to its foreign leverage. In the case of deductions for R&D expenses, transfers and licenses of resulting intangible property for foreign use are taxable under territorial tax systems so a full deduction for R&D is appropriate. Transfer pricing regulations generally require charge-out of U.S. general and administrative costs that are incurred to support foreign affiliates, providing an appropriate matching of income and expense. Finally, limitations on deductions for salaries relating to general and administrative expenses could encourage the movement of headquarter jobs to foreign locations that provided a full deduction for these activities, a result that may be in opposition to the intent of the territorial tax system.

4 See, Statement of David G. Noren, "Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Select Revenue Measures of the House Committee on Ways and Means," November 17, 2011.

5 This is achieved by an 85-percent exclusion of earnings. The provision disallows foreign tax credits associated with the 85 percent excluded income.